Controverses des Sexes Masculin et Foemenin

Controverses des Sexes Masculin et Foemenin

Gratien Du Pont

Paris : Gilles Corrozet : Jean III Du Pre : Vivant Gaultherot : Ambroise Girault : Maurice de La Porte : Alain Lotrian : Francois Regnault : Pierre Sergent, 1541

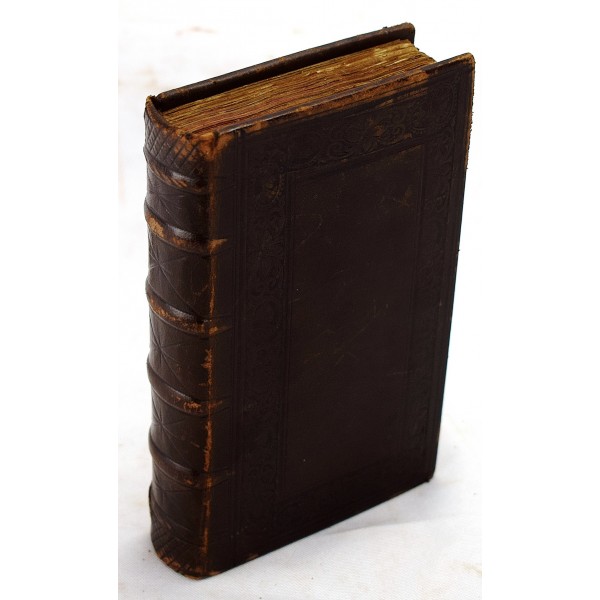

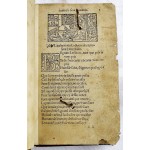

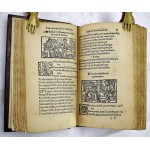

[Anti-feminist, misogynist literature] 3 parts in one volume. Bound in later calf, decorated in blind. Good binding and cover. Lacking first title. 264 leaves. 103 woodcuts illustrations. Worming to leaves Aii & Aiii. Early marginalia on rear end page. Refs: Brunet II, 251-2. Brun, p. 174. Dauze, 398 p. <br> First printed in 1534, Du Pont's work was a widely successful in the 16th century. Du Pont's Controverses was printed in 19 editions. In this work Du Pont brutally attacks the women of Toulouse, their vices, crimes, in verse. Dumege states in the Biographie Toulousaine: "Gracien Dupont ... displayed himself not only as ungallant, but also as a bad poet. Embittered no doubt by his ill success with the ladies, deceived by them, and perhaps their laughing-stock, he intrusted his revenge to his pen, and used it only to insult the women, the usual recourse of those whom they have maltreated. His indignation, which not even the muses favored, for they too showed themselves fickle to the noble Dupont inspired him to write a satire, published under this title: "Controverses des sexes masculins contre le feminine" a wretched piece of work from every angle, and one which proved to those who read it, to what extent the ladies were right in laughing at the expense of such a detractor. Dupont judged otherwise, and his spleen not yet being sufficiently vented, he launched a second diatribe entitled: "Requete du sexe masculin contre le feminin." This multiplicity of editions proves nothing in favor of the work, but simply indicates that the ladies have a multitude of enemies always delighted to hear them maligned; perhaps too, at that time every abandoned lover purchased a copy of these satires... Dupont, in a preface tells us he had travelled little; it was useless to say that he had almost always remained in his own province; so much the worse for him; that he had not studied much; one would have guessed that without any trouble. Two reasons, he continues have prompted him to write: the first is to give young men models, examples of all sorts of rhymes, or of every variety of verse. Certainly he might have dispensed with it, posterity would have picked no quarrel with him for keeping silence. The second reason, and forsooth the real one, is to exhibit the character of wicked women, their malicious tricks, their infernal spirit, the snares which they spread, and the secrets of their conduct. This author did not spare them; he is even unwilling to admit that they have been created, like man, in the image of God. 'The devil himself,' he says, 'had the care of shaping their persons.' Du Pont raises the question as to whether a man should marry or not, and answers it in the negative. A wise man would do better to live a life of celibacy than to have his days poisoned by woman, who is less of companion than shrew. Not content with dealing with woman generally, the author enters into an historical survey, recounting what both sacred and profane authors have had to say to the disadvantage of women." - John Dawson, translating Dumege, "Toulouse in the Renaissance," Columbia, 1923. 180-181 p.